Making precision ag accessible

Precision agriculture involves the methodical application of inputs – the exact amount to a particular part of the plant at the optimal time. It also calls for the use of diverse technologies in real time – such as GPS, drones and specialized cameras – offering the farmer accurate data to help reduce employment of agricultural additives and, by extension, damage to the surrounding ecosystem.

In May 2016, Costa Rica’s Development Bank approved funding for the Precision Agriculture Center at EARTH University’s La Flor campus, with the intention of improving the productivity of small and medium-sized family farms in the surrounding province of Guanacaste.

Agriculture in Guanacaste employees 28,000 locals and utilizes 80,260 hectares – 16 percent of the country’s total agricultural area. Principal crops include sugarcane, rice and melon.

The Precision Agriculture Center

Costa Rican EARTH grads Eduardo Villalobos (’11), Karim Abdalla (’16) and Carol Fuentes (’16) currently work at the Center, under the direction of professor Johan Perret, Ph.D.

New informational technologies allow for the documentation of growing conditions, along with the inventorying of nutrients and control of water supplies. The latter is of vital importance to the province of Guanacaste, where the sky offers little rain during the majority of the year. In short, precision ag initiatives can help farmers boost their lands’ resilience in the face of climate change.

Additionally, the Center promotes governmental investment in sustainable agriculture, encourages the study of precision ag in educational institutions, motivates young people to choose an agricultural career, serves as a gatekeeper of cutting-edge information, incentivizes the creation of more small agribusinesses and facilitates collaboration between them.

How does the Center work?

The data collection process for precision ag is divided into 12 steps:

- The work areas (local farms) are selected. Of each participating property, half will be cordoned off and treated traditionally by the farmer – servicing as the control group. The remainder will be managed by the Center according to precision ag best practices.

- Geo-referential samples are taken at four levels: soil, plant, drone and satellite – allowing for the comparative analysis of information.

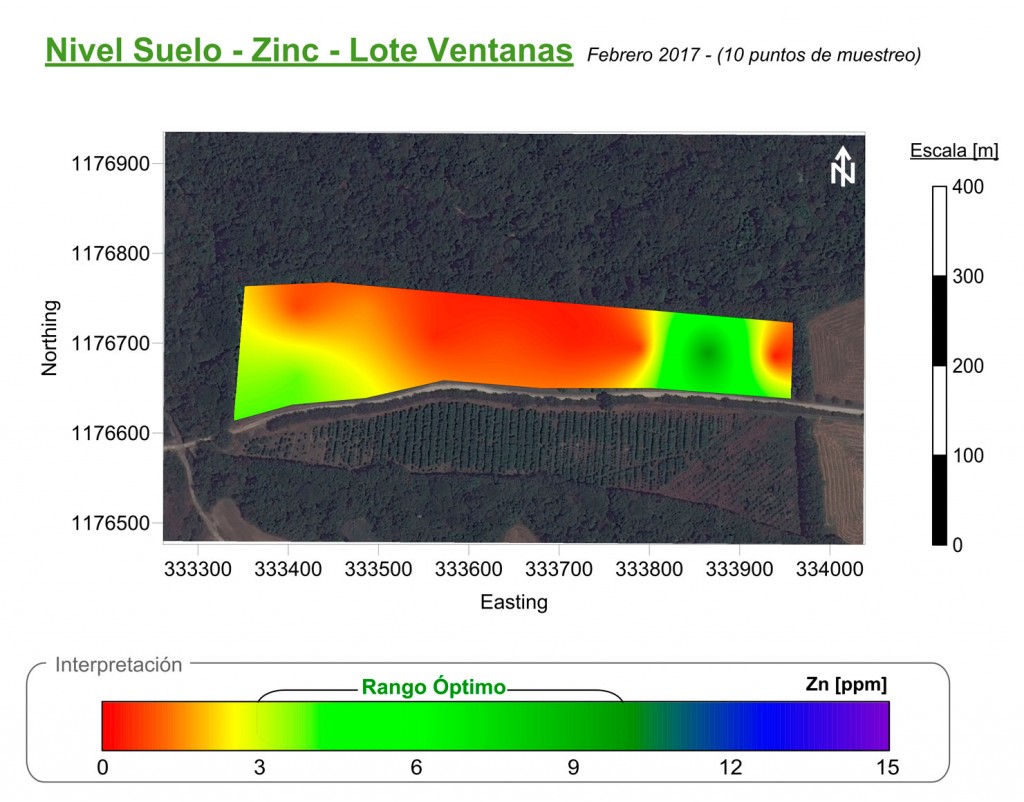

- Soil level: Chemical analysis of nutrient content in soil, as well as of physical properties such as texture, color, moisture, density, porosity, etc.

- Plant level: Chemical analysis of nutrient content within the plant, as well as information along the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

- Drone level: Multispectral, thermal and RGB cameras take photos of the property.

- Satellite level: Allows for the download of bird’s-eye images corresponding to the dates of the samples.

- In the lab, the drone-captured photos are edited and arranged into a mosaic, forming a larger picture of the property.

- The photos are used to make maps that facilitate observations (for example, of nutrients and their distribution in area), thus pointing out any inadequate camera coverage or present risks.

- Fertilization maps – with information on nutrient dosage and optimal distribution – are created.

- All the prepared maps and gathered information are delivered to the farmer where the Center will discuss plot management decisions with them.

- A plot management plan is drawn out from the recommendations, and simplified maps are made.

- With the simplified maps, application zones are measured and marked. The inputs are applied and, in time, the results can be analyzed.

Since last year, the Center has been working with 10 farms in Guanacaste selected according to established criteria.

Spreading the EcoArroz gospel

Andrés Vásquez is an agronomist. For 21 years, he has been growing sugarcane, grass and rice on large plots of land in Guanacaste. In 2012, he initiated growth trials of rice without synthetic pesticides (known as “EcoArroz”) to protect the fish populations living near his plantations.

“I started experimenting with certain biological methods to control insects and bacteria, to counteract fungi,” Vásquez said. “It was so successful that I decided to convert my entire production.”

For transforming his 300 hectares into a pesticide-free operation, Costa Rica’s Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock bestowed Vásquez with the Medalla del Mérito Agrícola (Agricultural Merit Medal) in 2016. He says that, thanks to the insights gained from precision ag, he now knows to add more nutrients – such as phosphorous – to the soil to boost its productivity.

“Precision agriculture is important because you start to save resources by using them only when necessary. It excites me knowing how everything will turn out. Even though the process is complicated, it offers many advantages,” he added.

Among its advantages, precision ag helped Vásquez (pictured) boost his harvest by 33 percent and increase his profits by $200 per hectare.

Vásquez believes all farmers, no matter the size of their terrain, should be encouraged to eliminate their pesticide use by implementing precision ag.

“I’m gladly giving talks at universities and to students who visit me. I also offer trainings to farmers because what interests me is not only my product, but also people producing in a less toxic way – this way, we win as a planet because it’s healthier, employees no longer lug around vats of poison on their backs, and you’re guaranteed to not be eating that poison. It’s not that many producers don’t think about the planet; it’s that they lack the understanding of how to produce sustainably in practice.”

Vásquez joined the Center’s efforts to promote precision ag because he values scientific research and recognizes the health benefits of consuming less pesticidal residue.

“A balanced and healthy plant gets sick less, thereby requiring fewer chemical additives,” he said. “It all adds up.”

Agriculture needs young people

The 2014 Costa Rican Agricultural Census, commissioned by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC), revealed the average age of agricultural workers in the country to be 54 years old, with 22 percent of respondents older than 65.

As part of the motivational activities, teachers ask for to-scale representations of ideas that should be implemented at the high school. The photo shows one such project in which a student built a mock greenhouse and hydroponic system. “This helps students visualize the projects at their real size. By the time they reach the theoretical part of the lesson or course, they have already learned many of the concepts on their own,” Núñez said.

For Costa Rica’s Ministry of Education and the teachers of Guanacaste, it is important that young people let go of their negative misconceptions of the profession and take up the work – in many cases continuing in their parents’ footsteps. To help achieve this, the Center is collaborating with the Professional-Technical High School of Liberia, to motivate its students toward agriculture through a technological focus while also underscoring the science’s necessity for feeding the world. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, from now until 2050, the world must produce 70 percent more food to feed an additional 2.3 billion people who will inhabit the planet.

Luis Guillermo Núñez is an agricultural sciences teacher at the school in Liberia.

“We are working to remove the prejudices that exist toward farmers and agriculture in general. There are many professions that depend on them. Young people need to understand that traditional agriculture has changed radically. It’s no longer just a pick, a shovel and a machete – today many production methods exist,” Núñez said.

At the school, students from seventh to ninth grade complete general courses to discover their affinities. Those courses – known as exploratory workshops – survey the fields of agriculture, tourism and bookkeeping, among other industries. When starting tenth grade, they must declare a specialty, one they’ll pursue for the following three years, until graduation.

For the past few years, a decreasing number of students has opted for agricultural specializations, to the point that numerous related specialties are no longer offered by the school.

José Eduardo from the Center explains a concept during a training session for students from the technical high school.

“The Precision Agriculture Center has helped my students by giving them access to equipment. We don’t have the resources to acquire drones ourselves, for example. The practical interaction the students have is super valuable,” Núñez said. “At the Center, they learn by doing, which is the heart of EARTH University. When the kids go to the field, they complete their assignments under the Center staff’s supervision, becoming members of the team in the process and confronting real-life challenges.”

Available subjects include agroecology, animal production, and irrigation and drainage, among others.

“We encourage them to choose specialties crucial to the area. The kids who have worked in the Center are really motivated to continue studying agriculture – including the girls. Five of them even want to apply to EARTH,” he added.

The technical school’s students stop for a photo during a tour of the Center at EARTH’s La Flor campus.

“We teach the students that they don’t need a huge plot of land in order to farm. They can produce vertically or have animals in stable systems. Many of their parents have farms, and the students can pass on their new knowledge to them, especially when it pertains to land use and water conservation,” Núñez said.

Even small farmers can do it

Miguel Salazar has been farming rice for 19 years in Asentamiento Tamarindo, a township in Guanacaste. He employs four people on his 5.5-hectare plot.

His farm was selected for inclusion in the precision ag study.

“I’m very pleased to be part of the Center’s research. Half of my farm is being managed by them; the other half I am working as I always have,” Salazar said.

One of the Center’s greatest lessons for small-lot farmers is the importance of measurement and control. They want those farmers to improve their records regarding when they fertilize, how much, etc. These same farmers also need to be prepared to face the fallout from climate change. In Costa Rica, the rainy season has been intensifying, causing significant crop loss. In 2017, Hurricane Nate alone destroyed 3,000 hectares of rice across the Central American nation.

“Climate change reduces our earnings and spikes product cost,” Salazar added.

“As farmers, we rely a lot on hope. Climatic changes are causing us to pray for less rain each winter and fewer hurricanes,” Salazar said.

Compounding that concern is the necessity of producing high-quality rice. Even small-lot farmers need to produce goods that are differentiated in some way from those of others. Salazar believes the application of precision ag on his land will generate more nutritious and desirable rice for consumers.

“Even though we rice farmers are very competitive, we’re always eager to learn. I urge the others to work with soil analysis and take advantage of the technical assistance from the Precision Agriculture Center for better their crop yields,” Salazar said.

Looking to the future

The Development Bank’s agreement with EARTH on this precision ag project expires in mid-2018, thus ending financing to the Center. To continue its services to the public, the Center’s staff is working to attract new farmers, small businesses and educational institutions and draft collaboration agreements.

Over the coming months, the project will continue monitoring the 112 selected hectares, as well as upskilling farmers, students and local businesspeople through workshops and trainings.

If you are interested in obtaining more information about the Precision Agriculture Center at EARTH La Flor, please contact José Eduardo Villalobos at jvillalobos@earth.ac.cr or +506 2713-0486.