Because it can decompose organic matter, fungi are the beginning and the end of all living things—and sometimes of non-living things. That’s how fascinating they are—silent organisms that are neither animals nor plants; so complex and diverse that they have their own kingdom. It’s hard to imagine that beneath every step we take, fungal networks extend over 400 kilometers per cubic meter. Over 100,000 species have been discovered, and at least 2,000 more are identified each year. They seem to be infinite in form, color, and size.

At one of the educational farms on the Guácimo Campus, Chemistry Professor Jessica Villegas dives into the jungle with passion and excitement, searching for different types of fungi. Every time she spots a new species, she shouts it out like a child discovering a treasure. Because in her worldview, fungi are exactly that: treasures to be studied, cultivated, and understood. Under the guidance of Professor Villegas and Properties of Tropical Soils Professor Johan Perret, a project has emerged that goes far beyond the lab—it’s an ecosystem of ideas, cooperation, applied knowledge, and collective dreams based on the boundless possibilities of the fungi kingdom.

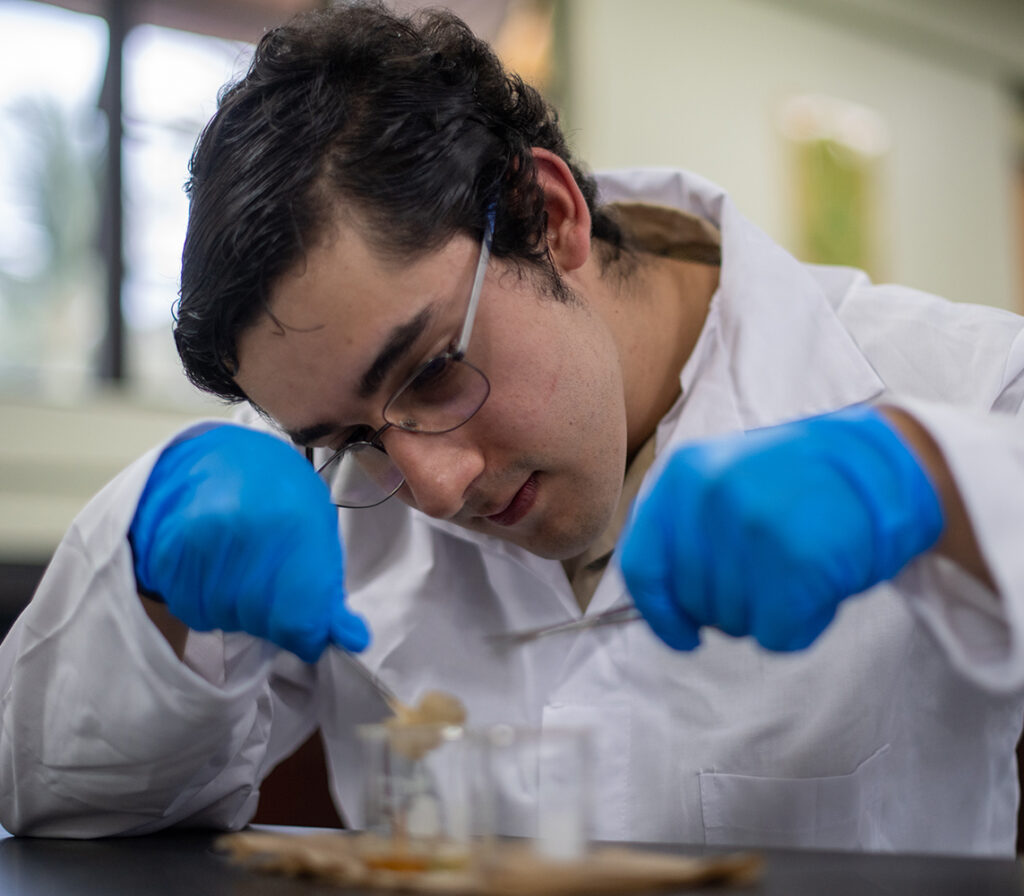

The project team, part of the University’s Research Seed Funding, includes both professors, fourth-year students Tomás Sánchez (Costa Rica) and Adam Vorster (South Africa)—who throughout 2025 will carry out their Graduation Project on innovative substrates for mushroom cultivation—and third-year student Pablo Culajay (Guatemala), who is passionate about fungi. Other students and faculty members have also joined to bring different approaches and perspectives to the project.

“At EARTH I saw that we have the right conditions: the climate, the resources, the support of the professors, and most importantly, the collective desire to innovate. My Graduation Project is not just an experiment with substrates like cassava, green banana, and sugarcane—it’s a door that opens for others to keep exploring. With this project, we can transform the way we produce food, offer a sustainable protein alternative, and regenerate our relationship with the land.”

Tomás Sánchez

Class of 2025, Costa Rica

The team is working to develop a cultivation system for the Pleurotus mushroom, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, using agro-industrial waste that is typically discarded: banana peels, coconut fiber, cassava pulp, coffee husk, hay pellets, and sugarcane bagasse—materials rich in complex carbohydrates like lignin and starch, essential nutrients for mushroom growth. But this project is not just about producing mushrooms—it’s about understanding them. Each substrate combination is being chemically analyzed to determine its nutritional value and capacity to feed mycelium (the underground or internal part of the fungus). The goal is to design scientifically sound formulas that respond to the actual needs of fungi.

The magic of the project also lies in its potential to scale. Once harvested, some students are exploring the possibility of developing flours and plant-based meat prototypes made from Pleurotus, to offer accessible, nutritious, and sustainable food alternatives. In addition to protein, edible fungi provide essential vitamins like D and the B-complex, key for the immune and nervous systems. This is especially important in a global context where food security and nutrition are urgent challenges.

“They’re always there—in plants, in food, when walking through campus. But we don’t know as much about fungi as we do about plants or animals. I realized I was ignoring an entire kingdom that’s part of our daily lives. I started researching out of curiosity, and now I see they have so many uses—from food to medicine and pest control. I want to keep exploring the fungi in this area, not just the commercial ones, because I’m sure they’re hiding much more than we know.”

Pablo Culajay

Class of 2026, Guatemala

That’s why, whenever they find an edible mushroom in the jungle, the professors on the project share potential recipes: an immune-boosting tea, an Asian-inspired soup full of nutrients, a simple garlic and butter dish, a vegan cheese made with fungi and almonds, and many others.

Another key aspect of the research is that the substrate they’re creating is not discarded after use—it’s transformed. In collaboration with other projects, they’re testing its ability to inhibit Fusarium, a pathogenic fungus that affects crops like tomatoes. The idea is to extract bioactive compounds from the post-harvest substrate to use them as biofungicides. In this way, initial waste becomes raw material, cultivation becomes nourishment, and residue becomes a solution. Nothing is wasted.

One of the project’s biggest challenges is infrastructure. Growing mushrooms requires specific conditions for temperature, humidity, and cleanliness. Spores, like ideas, are delicate and sensitive. That’s why a specialized microbiology lab for fungi is being planned, with dark incubation rooms, fruiting areas, and post-harvest zones. The location has already been identified at the Crop Farm on the Guácimo Campus, and the dream goes further: a comprehensive research center, serving as a mycelium bank, chemical analysis lab, and educational platform.

“I want to take advantage of all the technology we have here at the University and the experience and knowledge of our professors to develop a project that can help my community with an alternative food source.”

Adam Vorster

Class of 2025, South Africa

“Fungi can absorb heavy metals, clean polluted waters, produce medicine, serve as biomaterials, and feed the world,” says Professor Villegas.

What is sprouting at EARTH is not just Pleurotus cultures, but a new generation of young scientists with social sensitivity, technical creativity, and a deep connection to the land and its potential. The genuine interest of these young people and the faculty in fungi—humble, invisible, essential beings—is key to reimagining food systems and building a more sustainable and respectful future on Earth.